|

Africa's

Eritrea Revels in First Tastes of Peace and Freedom

Byline:

Christina Henning/For The News Tribune

Published

8/15/93

"Cappuccino with cognac?" the Eritrean waiter

asked. This question will be a shock to your system if

you've come, as I did, from neighboring Sudan, where drinking alcohol can get you as much as 40 lashes.

Only 25 minutes away from

Sudan

and the Sharia (Islamic Law), you can experience the full

excitement of Africa, yet have all the comforts and

flavors of Europe. Compared to the disorganized atmosphere

of

Sudan, Eritrea

will give you back a sense of familiarity. It's a country

where nothing requires a bribe, and prices are fixed for

everyone, even the foreigners.

Eritrea

is located in the Horn of

Africa on the west coast of the Red Sea and is roughly the

size of

Mississippi, with a coastline of 1,000 kilometers. It borders

Sudan

to the north,

Ethiopia

to the south and Djibouti

at the extreme southeast tip. The name Eritrea

was given by the Italians and comes from the Greek word

for "red." It is also a new member of the

community of nations. In April, following a United

Nations-monitored referendum,

Eritrea

's voters overwhelmingly declared their desire to become a

sovereign nation, free from Ethiopia.

The

country was under complete Italian control from 1890 to

1941. This explains why

Asmara, the capital of

Eritrea

, is called Little Rome and reflects the flavor of the

Italian Renaissance. It is perched on a plateau 2,300

meters above sea level and experiences a cool and healthy

climate year-round. The sidewalks are tiled and lined with

well-manicured palm trees, open piazzas and outdoor cafes

where you can sip cappuccino with cognac, eat pastry and

brush up on your Italian with old Ethiopian and Italian

men. The bars are open until the wee hours and offer

Saturday night dancing.

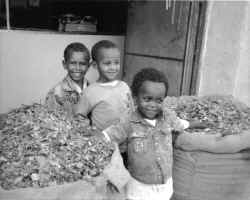

The general street life has a carnival-like atmosphere

that increases in tempo as the evening progresses. Germa

Asmorom, executive producer at the only TV station in

Asmara, said this about the city's excitement before the vote:

"Just wait until after the referendum this year; it

will be like Rio De Janeiro." The celebration continues.

However, not everyone shares Asmorom's enthusiasm for the

carefree behavior of the Eritreans. "I would not

bring my family into this kind of environment. They drink

all day . . . to forget the past," said Abduhla

Ibrihim, a Sudanese embassy official in Asmara. "Forget what? Forget 600 years?" Asmarom

snapped. "This is part of our heritage!"

Remarkably,

Asmara

was untouched by Eritrea's 30-year war (it ended in 1991) and has the look and

feel of an oasis, surrounded by the sands of conflict.

The reason for the celebrations has to do with the

homecoming of a large number of Eritreans who have been

refugees in

Sudan, the Middle East, Europe and America

for up to 30 years. These are the people who gave

financial support to the revolution and the families left

behind.

My hotel,

the Lul Leghesse in central Asmara, is filled with Americanized Eritreans, speaking broken

English with a variety of regional American accents. Their

teenage children parade through the hotel lobby displaying

the trendiest American fashions, while the parents are

overwhelmed by meeting family members and childhood

friends they haven't seen in years.

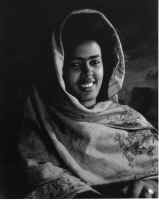

Neghisti

Seqoar, an office worker from

San Francisco

, has come back to Eritrea

after 15 years in exile to take part in the referendum. We

meet in the hotel bar for a cappuccino. Neghisti walks

over and greets me, pushing her right shoulder into mine

and then repeating the same movement with her left

shoulder. It's the Eritrean national greeting. "I am

so happy that we have our country back! I feel so

invigorated! I

gave up my job and put everything in storage. I may be

here for three to seven months, but who knows?" she

said. "Most likely I will go back to America. The Americans have been good to me."

Asmara

is host to visitors from many other Arab countries. The

wealthy Sudanese choose Asmara

for their honeymoons. The Persian Gulf Arabs escape to Asmara

for the nightlife and freedom that's unavailable to them

in their Islamic homeland.

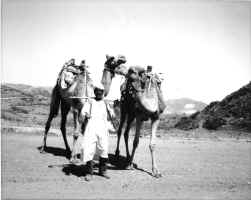

But outside this sophisticated metropolitan hub is still

the old

Africa, untouched by the modern world. A few kilometers past the

modern walls of Asmara

are typical Eritrean villages, with scattered round huts

made out of straw and mud. Nearby, Christian and Muslim

villagers work the fields together with age-old tools

planting wheat, lentils, linseed, peas and beans. The

nomadic caravaners on camels, called "ships of the

desert," move silently past the villages. But outside this sophisticated metropolitan hub is still

the old

Africa, untouched by the modern world. A few kilometers past the

modern walls of Asmara

are typical Eritrean villages, with scattered round huts

made out of straw and mud. Nearby, Christian and Muslim

villagers work the fields together with age-old tools

planting wheat, lentils, linseed, peas and beans. The

nomadic caravaners on camels, called "ships of the

desert," move silently past the villages.

Eritrea

is made up of nine major ethnic groups: Afar, Bilen,

Hadareb Kunama,

Nara

, Reshaida, Saho, Tigre,

and Tigrinya, each with its own traditional culture and

language.

Religion

is divided equally between the nomadic Muslims in the

lowlands and the Orthodox Christians who split from

mainstream Christianity in the sixth century A.D. and are

related to Coptic Christianity. A small percentage are

animists, believing in the existence of spirits and

demons.

The Afar

tribe enjoy an interesting reputation for collecting human

testicles as trophies. They are traders who wander freely

with their camels between

Eritrea

and Djibouti. Yet these different groups with a wide variety of

backgrounds have struggled together as Eritreans against a

series of colonial oppressors: the Italians, the British,

and the Ethiopians.

Two hours

from the festivities of

Asmara

is Massawa, the main port of entry on the

Red Sea

coast. In its last year of war, Massawa became the most

savage battlefield, as Soviet-made Ethiopian

fighter-bombers dropped napalm and cluster bombs on

civilians. Massawa was captured by

Eritrea, and the ghostly shells of houses and churches stand as a

memory and symbol of Eritrea's liberation. And for foreign visitors, Massawa is a

window that will give them a glimpse of the war and the

suffering it has produced.

The

Eritreans are celebrating the end of the longest ongoing

war in modern history. They are celebrating Eritrean

independence and the homecoming of their displaced family

members. How long the celebration will last, or what

happens after that, is anyone's guess. Now is an opportune

time to visit Eritrea

and join the swirling carnival of laughter and merriment.

As I

approach the

Asmara

airport for my flight back to Khartoum,

Sudan, I have the urge for one more cappuccino with cognac.

Worse yet, I want to go back to my hotel and fill my water

bottle with it. But visions of 40 lashes in the public

market, plus the threat of having my passport marked as an

undesirable, stopped me. With the best intentions, I faced

customs at the Khartoum

airport. The customs official dressed in her Islamic hijab

(long, loose, flowing clothing, with the head and hands

covered) jolted me back to reality. "Are you carrying

any beer, wine or cognac?" she growled at me.

"Of course not," I snapped back at her. "I

don't drink!"

If you go ...

*Visas are required of American citizens visiting Eritrea. Call the Department of State in Washington,

D.C.

, at 202-647-5225 for up-to-date travel information. The

Embassy of Eritrea in

Khartoum

is located in Khartoum

2, near the UNISEF office, and grants visas in 24 hours.

You need to bring a letter of introduction from the

American Embassy (phone 74611 or 74700), 200 Sudanese

pounds, and two passport photos.

*Several airlines - Sudan Airways, Ethiopian Airlines,

and Lufthansa - fly into Eritrea

from

Cairo, the hub for all travel in the

Middle East. The best deal as far as money goes is Sudan Airways. Be

forewarned that it is referred to as Insha'alla Airways.

It means the plane leaves when Allah wishes it. Delays of

many hours are not unusual.

*The Eritrean Tour service is located on Liberty Avenue

No. 61, in Asmara

(phone 11-99-99), and will arrange tours, accommodations,

and car rentals.

*Some of the world's natural wonders are close to

Eritrea, including the Danakil Alps and Africa's

Great Rift Valley. And for the adventurous, there is a bus that leaves from

Asmara

for Kassala at the Sudanese border. The trip takes three

days and two nights through mountains and desert roads

that are unpaved.

c.

2006, Christina Henning

|

|