|

Journey

to Sudan:

|

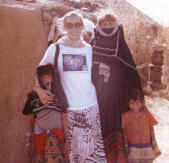

In

Kassala, the author stayed with Amara and her two

children. |

If

You Can Cope with Bad Hotels, Cramped and Lingering Train

Rides, Tedious Days of Processing Paperwork, and the

Threat of 40 Lashes for Having a Beer, This Is the Trip

for You Because the Friendliness and Hospitality of the

Arab People Can Make It All Worthwhile

By Christina Henning

for The News Tribune

"Why are you traveling to Sudan? And why are you

without your husband?'' demanded the Egyptian customs

official. These two questions illustrated the official

Egyptian view of my trip to their neglected neighbor

Sudan

, the largest country in Africa, with more pyramids than

Egypt

and a nation of 500 nomadic tribes.

I was not prepared for the barrage of zealous officials

that preceded boarding of the

Lake

Nasser

steamer from

Aswan

,

Egypt

, to Wadi Halfa,

Sudan

. The steamer is a human zoo and can be an intimidating

experience. Scurrying on and off the steamer were clusters

of men, bent over with the weight of 200-pound bags of

flour, their heads wrapped in bright turbans of lustrous

Egyptian cotton. Truckload after truckload of colorful

shoes and mats were loaded for

Sudan

, causing a delay of five hours. One worker fainted, but

no one came immediately to his aid. Eventually security

officers escorted us through the congested mass of people

and to our cabins. We arrived in Wadi Halfa the next

morning.

Travelers

to

Sudan

must be prepared for countless delays, crowds and

bureaucratic red tape. There is also some danger; the

United States Department of State warns travelers to avoid

Sudan because of the risks of banditry, terrorism

(primarily due to the ongoing civil war in the southern

regions) and strict curfews, which if violated, can lead

to detention by authorities.

Despite these problems, I am attracted to

Sudan

for its people. And even with the anti-Western propaganda

espoused by the government, an atmosphere of genuine

hospitality and friendliness prevails, surpassing all

other Arab countries I have visited.

For people traveling on the cheap to Wadi Halfa, there are

the

Nile

and Wadini Hotels. Women and men traveling together have a

difficult time finding accommodations. Even married

couples who don't have documentation are often refused a

hotel room because of the strict moral codes of the

Sudanese people.

For

the more affluent traveler, and for those in a hurry, it's

best to fly from

Cairo

to

Khartoum

, which offers the Meridien and Hilton hotels and the

famous Acropole Hotel.

My next destination was

Khartoum

. We were told that the train, the Khartoum Express, would

take three days and two nights to

Khartoum

from Wadi Halfa. Our trip lasted five days and four

nights. Aside from scheduled stops, it came to a

screeching halt five times a day for prayer, broke down

numerous times, stopped so that desert sand could be

shoved off the track, stopped to hunt for lost wagons and

occasionally shut down when the conductor felt he needed a

nap.

I

couldn't help but admire the women in my eight-person

cabin. I never heard a word of complaint about delays,

breakdowns or the general discomfort of the journey. The

seats are uncushioned, there's no leg room and you sit

knee-

to-knee with the passengers facing you. But these

travelers seemed unconcerned, even when someone else's

feet ended up in their laps! At night two women slept on

the floor between the seats and the rest of us managed to

contort our bodies into shapes I never thought possible.

While

I was sitting in the desert during one of the train's

breakdowns, decoratively scarred tribal women walked over

and greeted me, extending their right arms and touching my

left shoulder with their hands, then moving that hand to

their hearts. It's the Sudanese national greeting. The

hand on the shoulder means I have no weapon; the hand on

the heart, I come in peace. They made a fire under a small

pot to boil water for tea or coffee to share with me.

As the hours passed, the circle of women and children

around me grew. Men usually kept their respectful

distance. If one decided to come closer to take a better

look at the howaja, meaning white person, the women would

quickly shoo him away.

The

desert around the broken-down train started to have the

appearance of a refugee camp, as hundreds of people

scattered around putting up temporary shelter. Being the

only foreigner, I was the center of attention and the

source of much amusement, especially when the women

discovered hair on my legs. Arab women remove all body

hairs with a paste made of lemon water and sugar.

Finally we rolled into the

Khartoum

station and the people, lulled into a stupor by the

constant lurching of the train, came alive with laughter

and singing. To everyone's amazement, we were told that we

couldn't leave the train because it was past curfew time.

Curfew starts at 11 p.m. and ends at 4 a.m. It was 11:10

p.m.

Khartoum

houses one-fifth of

Sudan

's total population. It's the meeting place of the Blue

and White Niles, described in Arab poetry as the longest

kiss in history. The

Nile

, with a total length of 4,000 miles, is the longest river

in the world and runs through the country from south to

north

The

British left their mark on

Khartoum

by laying the streets out in the shape of the British

flag. General Gordon's palace today is the People's

Palace. In

Khartoum

, office work stops and shops close at prayer time, and

the limited number of broadcast channels on radio and TV

make sure that the people never forget the importance of

Sharia (Islamic law) and general Islamic practices. For

non-Muslims, it can be a suffocating environment. On the

other hand, Islam unites people across class lines.

Sudan

has been burdened with

political turmoil and economic chaos throughout history.

It's a country said "to change presidents and

governments every Friday after prayers,'' according to a

ticket agent for Sudan Airways who didn't want his name

revealed.

"I do not make any decisions between Fridays and

Sundays, because if there is a new government, there will

be new laws and rules to follow,'' said the ticket agent

with a shrug of his shoulders.

Problems,

however large, seem to be taken in stride by the Sudanese.

Sudan

's present government came to power in a June 1989

military coup headed by 45-year old Lt. Gen. Omar Hassan

Ahmed al-Bashir. The government is still in the process of

transformation. Sharia has been established as the code

for public and private life.

Practices

which are seen as non-Islamic have been eliminated. For

instance, under the new Public Morality Act, women's

clothes must be loose-fitting, not similar to men's

clothing and must cover the whole body. As a foreigner,

you are exempt from the Islamic dress called hijab, but

you are expected to cover up.

All

alcohol is banned. The law states that any person who

drinks alcohol or gains possession of alcohol shall be

flogged 40 lashes. Foreigners are not exempt from this.

Leaving the train when curfew finally ended, exhausted

from sitting up four nights without any real sleep, I

collapsed on the desk of the El Sawahali Hotel in downtown

Khartoum

begging for a room. But first, the manager had to pause

for his daily prayer.

My

room had a small sink with a tap about two feet above the

basin, two beds without blankets, but with clean sheets,

and a balcony overlooking

United Nations Square

and heaps of stone rubble. When I turned on the tap, there

was no water. I found the manager in the kitchen, and he

was extremely apologetic. He told me that all of

Khartoum

was out of water at the moment. The Egyptians warned me

that I could starve or be shot if I went to

Sudan

, but no one told me that I might not find any water.

"What about blankets?'' I whined. "I am sorry,''

he replied. "It is the new rule, all blankets in the

hotels of

Khartoum

have been confiscated by the Minister of Health.''

Eventually,

water was found, buckets were carried up four flights of

stairs, food was prepared and extra sheets were brought to

use as blankets. I was touched by the concern of my hosts.

In

Sudan

today, war, famine and natural disasters have played a

role in displacing hundreds of thousands of Sudanese

residents from the south

to the national capital of

Khartoum

. The majority of these are boys between the ages of 8 and

16. They roam the streets of

Khartoum

in packs during the day and in the afternoon gather around

the mosque where they wait patiently for trucks of food to

appear.

The

phenomenon of street children is a problem to be found

everywhere in the world, but the people of

Khartoum

cared for the children as best they could. The suggested

solution by the new government is to round them up and put

them into military service or similar institutions.

The

city itself looked distressed with unremoved debris from

buildings destroyed during the June 1989 coup. It was

especially desolate and eerie at night after curfew. The

general street life of a typical Arab city was absent.

Every

country in the world open to foreigners likes to pride

itself on its hospitality, but in

Sudan

it's for real. You will never be asked for a tip

(baksheesh, which is nothing but a petty bribe) as in

other Arab countries where hustling is an art.

If

you are looking for beauty, it's not in the temples or

museums of

Khartoum

but in the people's disarming kindness towards strangers.

My

eight days in

Khartoum

were occupied from 7 a.m. until the late afternoon at the

Alien and Security office were I had to register and apply

for travel permits. This involved numerous pieces of paper

to be filled out, stamped, certified and photocopied. Each

paper requires a passport photo.

Travelers

are not allowed to leave

Khartoum

or

Sudan

without travel permits. This means sitting in ill-lighted

offices with other worn-out foreigners clutching their

papers, outnumbered by bored-looking officials who will

demand a pen from you, use it to sign your permits and

keep it. I brought 25 pens, and left

Sudan

with one.

A

year after the gulf war,

Sudan

is still paying a high price for backing

Iraq

. The average citizens have been hard hit by their

government's choice, particularly the large number of

merchants whose livelihood depends on the trade routes

established by their ancestors and which are now closed to

them. It's no wonder the Sudanese are uncertain whether

Allah laughed or cried when he created

Sudan

, as an age-old proverb says.

In

spite of its negative aspects,

Sudan

is an adventurous, fascinating and extremely safe place to

visit. Because of its checkered political history and lack

of conveniences, travelers have been kept away from this

unexplored country. The only paved road in

Sudan

runs between

Khartoum

and

Port Sudan

, via Wad Medani, Gedaref and Kassala (in

Eastern Sudan

close to the Ethiopian border). The traveler can ride one

of the luxury buses that has windows, air-conditioning and

shock absorbers. The

trip takes eight to

10 hours.

Kassala

lies on the Sudanese-Eritrean border. The city is famous

for its jebels, cone-shaped hills and a variety of fruits,

including oranges, grapefruits, dates, pomegranates and

melons. The main tribes in the area are the Hadendowa,

Beni Amir, Shukriyya, Halanga and the Reshaida. I stayed

at the Noor Palace Hotel.

The

Reshaida tribe came to

Sudan

from the

Arabian Peninsula

about 150 years ago by ship with their camels and goats.

Today, they are still unwelcome guests living in Kassala

and areas of

Iraq

and

Ethiopia

. They are known for their silver jewelry and for breeding

the best racing camels.

In

Kassala I befriended Amara, who took me to her village

where I lived among the Reshaida for five days. The 20th

century has not intruded inside the Reshaida's tents.

Colorful mats and thick tapestries covered parts of the

sand floor. But outside, the camels were parked next to

their trucks. The men spend their days with the animals,

while the women take care of the finances. Each has her

own hiding place for her jewelry and money (usually

underground).

The

traveler today may wish to travel to far-away Kassala or

make a day trip

to

Khartoum

's sister city

Omdurman

across the two

Niles

. It's the old part of

Khartoum

with mud-brick buildings and narrow streets.

For

the mad shopper,

Omdurman

's Souk is the largest market in

Sudan

. You can watch craftspeople carving ebony and ivory,

goldsmiths and silversmiths shaping glimmering bits of

metal.

The

Souk is a meeting place for people from all over the

country selling and trading their local crafts. It's a

fascinating place to wander through, to see the people

from widely scattered cultures of

Africa

displaying exotic customs, from richly embroidered veils

to highly varied facial scars and intricate body

decoration focusing on the hands and feet.

The

market in

Omdurman

is known to have the largest selection of camels in the

world, and whirling dervishes perform their ritual dances

at Hamad En Nil Cemetery every Friday.

I

returned to

Khartoum

with only two days left on my visa and went to Sudan

Airways to book a flight to Wadi Halfa to meet the

Lake

Nasser

steamer back to

Aswan

. Even after my four weeks traveling in

Sudan

, I failed to remember that the words "hurry'' and

"speed'' do not translate into Sudanese. At the

ticket counter I was told that all flights to Wadi Halfa

were filled for three weeks and, scrutinizing my travel

permits, the ticket agent told me that he couldn't sell me

a ticket because I didn't have permission to be back in

Khartoum

. I did two things I advise travelers not to do: I became

hysterical and threatened to come back with an official

from the American Embassy. Several hours later I received

my ticket.

Having reached the

Lake

Nasser

steamer, my traveling companion and I threw ourselves into

our first-class cabin and on a berth that still had

remnants of meals on it from the previous occupant. I got

up to hang my coat on the closet door, and a rat jumped

out and disappeared underneath a mass of steel pipes.

Pressing myself tightly into the berth, I screamed at my

companion to "do something!'' A few minutes later she

returned with the burly ship manager followed by a bunch

of laughing Sudanese.

The

manager, trying hard to look serious, demanded to know

where the rat went. I pointed to the steel pipes, and he

got down on the floor and nodded his head. "You have

nothing to worry about; it went to the next cabin, through

that hole. If you give me some paper I will block the hole

so he doesn't come back,'' he said.

It had taken me eight days to get my travel permits in

Khartoum

. This time I was able to do it in three. I found myself

habitually lost in the city, spending hours with a

250-pound taxi driver who tried to convince me that he was

the Minister of Health. I wasted another day with a driver

who took the scenic route to the Alien office and in the

process got lost himself. By the time he found the Alien

Office it was closed but, by then, the driver had me

convinced he was the Minister of Information.

Two

days later, relaxing in the comfort of our hotel in

Aswan

,

Egypt

, my companion said, "Now that we know the system,

let's go back next year.''

© 1992, Christina Henning

Pictures © Christina Henning

|