|

YEMEN

One Tale in a Thousand

Author:

CHRISTINA

HENNING |

|

I was wearing nothing but a gold chain around my neck as

the fully dressed, saffron-headed woman shuffled toward

me. She pulled me by the hand through a maze of

underground passageways while I skated behind her on a

slimy stone floor, past mountains of shaved hair, into the

main steam room.

"Sit!"

she commanded, and began to scrub this infidel's body with

inflamed religious fervor and a steel-wool pad.

In San`a,

the capital of Yemen, Islamic tradition prevails. For three days a week, women

are permitted to use the public baths (hammam) to wash and

purify themselves. In times past, visits to the bathhouse

gave women a chance to escape from their secluded

dwellings. In the hammam they could shed their veils and

remove the yards of swathing fabric from their bodies.

Tradition

and change

This

tradition of women's all-day rituals has continued

undisturbed. Today, however, the bolts of discarded cloth

reveal slinky silk dresses and startlingly sexy underwear.

After

hours of scouring, steaming and kneading, Saffron's beauty

treatment left me limp and pliable. I was touched by the

bath aide's willingness to share her beauty secrets with a

stranger. However, we arrived at an impasse when she tried

to pull the hair off my legs. Glaring ferociously, she

dumped gallons of water over my head and marched me off

down a sultry, sloping tunnel to an adjoining chamber.

Murmuring

women leaned against stone troughs ladling water on each

other. Others were busily examining their bodies for

ungodly hair. Islam determines even the details of

personal hygiene. It is considered a sin to have hair on

one's private parts. Numerous dipilatory concoctions have

been invented over the ages, and some women were applying

the current favorite, a candylike paste of lemon juice,

water and sugar.

Naked

women and children drifted out of the mist from an

adjoining subterranean passageway and kissed my hands in

the traditional Yemeni greeting. I became the center of

attention, and the source of much amusement, when the

women discovered my lamentably hirsute condition.

The

one-woman battalion of the hammam flopped her arms up and

down, shooing away the women around me. Like a magician,

she produced a bowl of hair-eating paste from under her

many petticoats, intent on performing my last

purification. My hysterical and pathetic Arabic stopped

her. She threw her hands up in disgusted resignation and

disappeared into a foggy tunnel.

A series

of domed rooms led into a vestibule, where the women

rinsed, relaxed, discussed personal issues and world

affairs.

With a

lot of laughter and cackling, we exchanged cosmetics and

perfumes. After covering their faces and bodies with yards

of black fabric, one woman was indistinguishable from

another. I followed the dark figures up a musty granite

corridor to the vaulted stone entrance of the hammam, and

we stepped back into the outside world.

On the

street, women become ghosts again. Heads are bandaged in

cloth to the eyebrows. A dark stretchy gauze covers them

from neck to nose. Others wear all-enveloping enormous

black cloaks with matching scarves through which they can

see without being seen.

To

hard-core feminists,Yemen

resembles a throwback to the Neanderthal ages. Yet there

have been notable exceptions to the general rule of female

anonymity and subservience. The queen of

Sheba

set out from Yemen

on her legendary journey to visit King Solomon. In 1091

Malika Arwa became head of state and ruled for 47 years.

She held the royal title, Al Sayyida Al-Hurra, meaning

"the lady who is free." Historians claim that

Arwa never made an important decision without first

visiting the bathhouse.

In 1990,

with a stroke of a pen rather than a streak of bullets,

the former North Yemen

and the Marxist-Leninist South Yemen unified.

Aneesa

Ghanem, herself something of an anomaly as a Yemeni

feminist writer and activist, observed that "the

unification of the two Yemens

has been good for the country. But previously achieved

gains for women in their former south have been

compromised. The new Family Law has set women back

centuries. Now, I must get the written permission of my

husband, father or close male relative in order to

travel," explained Ghanem.

"When

it all gets too much, I run to Hammam Ali for a good

steam," she said.

No one

can determine how many wars have rolled over the country's

volcanic terrain and desert dunes, but the periods of

warfare exceed the passages of peace.

Remarkably,

life in the public bathhouses remains unchanged and

untouched by war. With peace relatively secure, the

government has launched a reconstruction program designed

to promote tourism. Europeans have already begun to

identify Yemen

as another French Riviera, and German families flock to

San`a during the Christmas holidays for its healthy

climate.

The

State Department advises U.S.

citizens to travel only with an armed guard outside of

San`a. This is not a destination for the timid. The path

to Yemen

is no intercontinental exotica route,

and thrill seekers are still able to satisfy their lust

for the unexpected. Intrepid individuals in search of

the wild and primitive will find a long shoreline, high mountains, deep gorges

and vast deserts. Yemen

is known as the "green land

of

Arabia

."

(Traveling

in Yemen with my bodyguard)

For an undiluted Arab experience, the Republic

of Yemen

is incomparable.

Travel in

Yemen

has to be undertaken on Yemeni terms. Socializing with the

locals in the underworld of San`a is one way to bridge the

cultural gap. The 17 bathhouses are modeled after the

Roman baths and are 400 to 1,000 years old.

Not all

of these establishments welcome foreigners. At the baths

near the Taj Talah Hotel, in the old city, I was met by a

vigilant community elder. He wore typical Yemeni garb -

sports jacket over a long skirt, a 10-inch dagger around

his waist and a cartridge belt over his shoulders. He was

tall, his face profoundly wrinkled and the color of

obsidian. He told my Iraqi companion, "No Westerners!

First they bomb Iraq, and now they have come to destroy our hammams."

A

crowd gathered and everyone took sides in the argument. I

walked away, unnoticed.

One

Yemeni defended the display of weapons.

"It

is part of our attire," he said. "A Yemeni

without his jambia [dagger] is like an Oxford

man without his tie."

Commenting

on the shrouded women, he said, "The restrictive

clothing of our women has nothing to do with religion.

This is tradition, and tradition is our identity."

To flout

tradition this strong is no small thing. This year, for

the first time, the female table tennis champion of the

Arab and Asian worlds showed up for a tournament unveiled

and wearing shorts. The two males on the podium presented

her with the trophy in stony silence.

But life

in Yemen

has its consolations; the table tennis champ and about a

hundred women rented a hammam for the day, to celebrate.

Lady Mary

Wortley Montagu observed in 1717 that the baths are truly

the women's coffeehouse.

For

today's Yemeni women, the hammam is not only a convivial

social center, but also a forum for ideas that might

otherwise find no expression here in the shadow of the

patriarchs.

|

If

You Go

Author:

CHRISTINA HENNING |

|

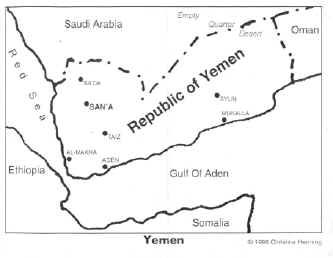

The

Republic

of

Yemen

is at the southernmost tip of the

Arabian Peninsula. The country shares borders

with

Saudi Arabia,

Oman, the Arabian Sea, the Indian

Ocean, and the

Red Sea.

San`a, the capital of Yemen , is

about 2,000 years old and is 7,200 feet above sea level.

Mountains surround the city, and parts of the highlands

are volcanically active. Hot springs

can be found here.

San`a offers the widest variety of hotels in Yemen.

The 270-year-old Taj Talah Hotel is in one of the

largest preserved medinas (the old city) in the Arab

world and classified as a "world heritage" by UNESCO.

The hotel has a garden restaurant, helpful kitchen staff

and a roof garden overlooking San`a's architectural

delights.

The Taj Talah is the potpourri of the Arab world and

attracts an assortment of characters usually found only

in spy novels. Journalists, the New York Bombay incense

crowd, expatriates, mysterious Iraqi businessmen with

bulging briefcases, ex-politicians in hiding, and

Algerian artists looking for asylum. Carlo Schellemenn,

a famous German painter, lived at this hotel.

Singles, doubles, and triples cost from $12 to $20.

Hammam Yasir and Shukr are said to be the oldest (about

1,000 years) bathhouses in San`a. Hammam Al-Maydan was

built in 1598, and Al-Sultan a hundred years later. Most

of San`a's 17 bathhouses are in the old city.

Yemeni hammams are built according to a traditional

plan. Three warm and three hot pool rooms in adjacent

rows, each with a changing room, meditation or prayer

room, lobby, furnace room and boiler room. Hypocausts

and vents direct the heat. Hot water flows to the pools

from the well and boiler via a system of pipes. Outside

of San`a, hot springs

provide the heat.

Bathhouse visit memorable

Western visitors rarely visit the bathhouses in Yemen,

which is a pity since the experience is pleasant and

memorable. On your first visit, you may feel more

comfortable if you hire a local guide. There is no fixed

price for the bath. Guests pay the bath keeper according

to their wealth.

Most Yemenis go out of their way to help and advise

foreigners. In return they want visitors to respect

their way of life.

Children have been known to throw rocks at foreigners.

Do not make the mistake of getting angry or hitting

them.

Men and women need to dress conservatively. Women should

wear head scarves and shapeless long dresses. Some

eateries may not serve a solitary woman. On buses, women

sit in the back and are not allowed in the bus-stop

cafeteria. Men bring the food to the women. This does

not apply to Western women. However, mimicking Yemeni

women socially puts everyone at ease.

American citizens need a visa to enter Yemen,

and it is easy to get one. Tourists with visas or border

stamps from Israel

will not be admitted. It is possible to apply for a second

U.S.

passport with blank pages. The visa application is filled

with the customary questions. Visitors to the

Middle East

are routinely perplexed about how to answer the question

"religion." It is perfectly safe to write your religion.

Stating "no religion" may not be acceptable.

For the latest information contact Embassy of the

Republic

of

Yemen, Suite

705, 2600 Virginia Ave. N.W.

,

Washington, D.C.

20037. Phone (202) 965-4760 or fax (202)

337-2017.

For the latest travel advisory and how to obtain a

second passport, call the Department of State in

Washington, D.C. at (202) 647-525 or the Consular

Affairs automated fax system at (202) 647-3000.

Yemeni girl

www.nwu.org |